For better or much, much worse, Frank Miller’s reputation has proceeded him in comics for something like 30 years. At its best, Miller’s name is a reference to a genre-blending master of form and function, who re-branded Daredevil as a character before permanently redefining Batman as a character and concept. At worst, his name is synonymous with Bush-era jingoism, Islamophobia, and the misogyny in Holy Terror! and the latter Sin City comics. For many comics readers, that second identity far eclipses his earlier works. Holy Terror! is genuinely a comic so bad that it made people forget that Batman: Year One is the greatest comic of all time and Daredevil: Born Again and The Dark Knight Returns aren’t far behind it.

Part of the problem is that so many of the things that make Miller’s most recent books objectionable, the seeds of his off-putting hatred and reactionary takes on gender, sexuality, race and war, are planted in his early works. Daredevil: Born Again treats Karen Page, at best, as a characterless, sexualized plot device and many of the women in Miller’s original Daredevil run don’t fare much better. It’s easy to claim that Sin City is serving up reheated noir genre conventions, but that doesn’t quite excuse the rampant use of rape and sexualized violence as both a plot-motivating force and source of karmic punishment throughout the run. Most visibly, it’s hard to deny the racially and culturally loaded imagery throughout The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Back.

Part of the problem is that so many of the things that make Miller’s most recent books objectionable, the seeds of his off-putting hatred and reactionary takes on gender, sexuality, race and war, are planted in his early works. Daredevil: Born Again treats Karen Page, at best, as a characterless, sexualized plot device and many of the women in Miller’s original Daredevil run don’t fare much better. It’s easy to claim that Sin City is serving up reheated noir genre conventions, but that doesn’t quite excuse the rampant use of rape and sexualized violence as both a plot-motivating force and source of karmic punishment throughout the run. Most visibly, it’s hard to deny the racially and culturally loaded imagery throughout The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Back.

For Miller’s fans and critics alike, The Dark Knight books, but primarily the vastly superior original book, Returns, serve as a rosetta stone, the story that feels closest to the writer’s worldview and the one that seems to offer up the most secrets upon being decoded. Both deal heavily with Miller’s personal politics, particularly his idea of the social and political Superman. Both explore the ideas of inept, weak, and compromised governments with no interest in serving the people they’re ostensibly elected to represent. Both attempt, to varying degrees of success, to critique the knee-jerk nature of media, particularly the 24-hour news cycle.

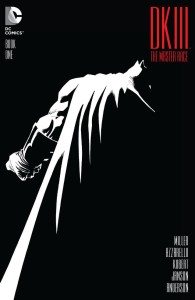

All of this makes the release of The Dark Knight III: The Master Race #1 into an event, for comics fans, hardcore comics analysts and Miller’s frequent, very vocal critics alike. I want to dig into what exactly is happening in this week’s issue but it’s almost worth actually digging into Miller’s takes on these characters and his alternate universe before trying to make sense of the new piece.

Now, personally, I’m not one to judge an artist’s work based on their politics but Miller’s beliefs are such an intrinsic part of his work that they’re worth digging into up front. Broadly speaking, Miller’s politics occupy the strange little intersection between far-right neo-conservativism and modern-libertarianism. That little corner of the political spectrum is where we get to Miller’s take on superheroes, namely that they represent incredible, near godlike figures of strength and ingenuity who can inspire others where no mere mortal can.

For Miller, Batman and Superman are a strange mix of John Galt and any number of Richard Wagner characters. That characterization, however, doesn’t make them infallible. In The Dark Knight Returns, Superman has been made a pawn of an impotent, out of touch Ronald Reagan. In The Dark Knight Strikes Back, Ray Palmer has been trapped inside of a petri dish by Lex Luthor but is able to help Batman in leading a revolution after he’s freed. These are superheroes that can be fallible but, more importantly, they are capable of being much more. In both The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Back, Batman inspires revolution against the federal government just by showing up. Much like Miller himself, his reputation far proceeds him.

Less concrete is Miller’s take on the media. Much like someone who gets almost sexual pleasure from pointing out whenever CNN fucks up, Miller’s criticism of the media has never quite evolved past the idea that sometimes TV news is bad, I guess. Seriously, Miller is mostly just obsessed with the idea that people argue on TV, often about not particularly important issues. In The Dark Knight Returns, that’s kind of the point. A critique primarily of Reagan’s focus on shadowboxing the dying Soviet Union while letting America’s cities descend into urban hellscapes, Miller uses the media as sort of a Greek chorus.

While Gotham slowly sinks even deeper into violence and vice, various experts and voices debate endlessly over subjects they have no control over. They shout, drowning out the page with heated dialogue, covering the horror of the everyday. It’s smart, at first, but doesn’t evolve. See, ideally, the voices should change. The Dark Knight Returns is entirely about how Gotham, and America, shift as Batman becomes more of a prominent force in the city but the media’s portrayal doesn’t. Sure, they talk about Batman more but it’s still endless, needless debate. It’s unclear over whether or not this was meant as Miller’s broader critique of the media or not but it doesn’t really work either way.

![[DC Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ba2459dfc7fc7606f4894a9b447931d0._SX640_QL80_TTD_-195x300.jpg)

The Dark Knight Strikes Back is even worse about this and it has the side benefit of really, really hating women. Most of the scenes with the media in Strikes Back focus on one of two things, either just narrating things that are already happening on the page and do not need to be explained further or focusing on the Superchix, a trio of women who are either dressed like superheroes or are superheroes. Seriously, Miller can’t figure out which one is which. It seems like Batgirl at least does things but the only thing any of them do in the series is argue about how they have the right to dress how they do, but it’s written in that way that’s super clear that Miller doesn’t think they do have that right. It’s obnoxious and one of the most grating bits of the series and, worse, it doesn’t really go anywhere. Even at the end of the series, nothing has changed with them, despite the fact that the president has been revealed to be a computer simulation and the human race has been brought to the brink of fucking extinction.

Goddamn, I hate most of The Dark Knight Strikes Back.

So, where does that put us with the first issue of The Dark Knight III? Well, it’s an odd blend of a lot of familiar ideas that are going to be instantly recognizable to readers, both if you want pure uncut Frank Miller or if you want to make fun of pure, uncut Frank Miller. There’s still a host of dialogue spoken by young people that sounds like it was written by someone’s not-particularly-with-it dad, there are a host of media figures shouting over each other and there are still pages after pages of brash, bone-crunching action but it’s all off, just a little bit. Reading The Dark Knight III after mainlining a reread of The Dark Knight Returns and Strikes Back, is kind of like having a dream about a comic that I know. Everything is there but things are just slightly off, it’s too close to the things we know but not everything is right.

![[DC Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/b90d7e7d6c305e5f749d2676599e185d._SX640_QL80_TTD_-195x300.jpg)

Most notable, the media scenes are chocked full of recognizable parodies of modern media figures. Your milage may vary on this and I can see different takes on whether this is better or not than Miller’s normal takes. On the one hand, there’s not any really blatant Jewish or Black caricatures which Miller and Lynn Varney would often depend on when illustrating these scenes but it’s also too specific, to the point where it just feels too of the real world. Having an only slightly different Bill O’Reilly bitch and moan about Batman isn’t really interesting or powerful. It’s just odd and feels like a conscientious bid for relevancy. The Kelly Ripa and Michael Strahan cameos are even more bizarre and unnecessary.

Similar issues plague the portraits of power and violence. There will be accusations that The Master Race #1 is an attack both on the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the power structures that seem to allow police to kill civilians but it doesn’t really. It’s a thoroughly toothless issue and even the final pages, a brutal showdown between a swat team and Batman, lacks those little flourishes that make these book’s something memorable.

And, honestly, that’s because Frank clearly didn’t write this comic. He’s been slippery and evasive about this in interviews but it’s fairly clear that his contributions to the script, if any, were minimal. This is a Brian Azzarello book through and through. The stabs at political relevancy and the poorly executed attempts to replicate vernacular are the most obvious clues but the script’s clear, passionate treatment of a variety of female characters also prove this isn’t much of a Miller book. All in all, it’s not a bad shift but it’s clearly not what you want either. Nobody, neither critics out for blood or fans eagerly awaiting a sequel, want to read someone doing a Frank Miller impression but that’s kind of what you’re left with. Despite his best efforts, Azzarello has never had the ability to make dialogue pop off the page like Miller can and Andy Kubert’s art never looks like anyone’s but Andy Kubert’s.

![[DC Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/DKTMR-1-19-1-3ca52-e1448923431140-470x306.jpg)

Much like I was forced to ask myself four years ago when DC announced Before Watchmen, I again question who this comic is for. To be frank, no one wanted or should want a sequel to The Dark Knight Strikes Back especially one that so loosely picks up only the smallest shreds of the plots and themes and no one was buying these books for anything but Frank Miller.

If DC didn’t have the confidence to let Miller write a book, fully knowing what problems were going to be in it, why release a comic that he was clearly barely involved in. It doesn’t really matter if The Dark Knight III is good or bad. What matters is that it’s not the comic you want, especially with that infamous name proceeding it.