Following

Release Date: 1998

Release Date: 1998

Cast: Jeremy Theobald, Alex Haw, Lucy Russell

Director: Christopher Nolan

Studio: Next Wave Films, Syncopy

Distributor: Zeitgeist Films (US), Momentum Pictures (UK)

Genre(s): Neonoir, Psychological / Crime Thriller

Rating: ★★★☆☆

Review Spoilers: Medium

IMDB | Rotten Tomatoes | Wikipedia

“The following is my explanation…well, my…my account of…well, what happened.”

The first spoken line of Nolan’s first feature film contains the very obvious pun and title drop. There is no doubt that trickery is at work in this tautly written and filmed guerilla neonoir set in London. Produced on Nolan’s own budget of about $6,000 and acted by a non-professional cast of his friends from University College London, Following offered a blueprint of the English director’s chief thematic predilections: duality, physical versus psychological identity, duplicity, delusion, non-linear presentation, and characters that cling obsessively to the romanticized narratives they willingly inhabit.

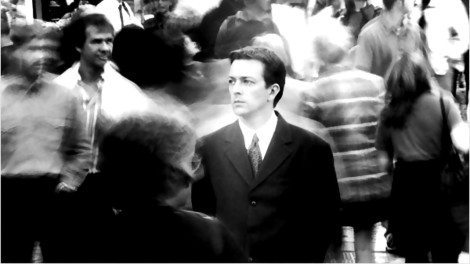

The protagonist is a greasy-haired, unemployed writer who calls himself Bill (Jeremy Theobald). Well into his late twenties and still living in post-university squalor, Bill is bored, uninspired, and disappointed in his mundane, empty life. In the post-credits and Nolan’s script, he doesn’t even have a name—he’s just “The Young Man.”

So “Bill” begins following random strangers on the street, initially to relieve his boredom and to collect material for the novels that are stuck in his head. Soon, this voyeurism grows into an obsessive hobby: “How can I explain? Your eyes pass over the crowd. And if you let them settle on a person, then that person becomes an individual. Just like that. It just became… irresistible.”

Bill’s stalking takes a turn when he is caught by one of his marks at a coffee shop: Cobb, a cat burglar with slick clothes and urbane diction played with charismatic verve by Alex Haw. In a most amusing confrontation (Bill: “I thought you looked interesting.” Cobb: “What, are you a faggot?”) Cobb seduces Bill into becoming his sort of brotherly apprentice.

“You take it away,” he evangelizes to a distraught Bill. “And show them what they had.”

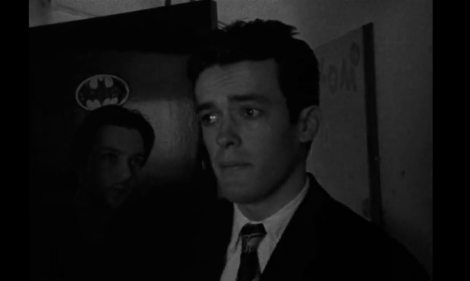

When Cobb instructs Bill to choose their next mark, Bill picks out his own one-room flat under the pretense that a banker lived there. It is here that we get a sense of Bill’s own self-dissatisfaction and his relatable need for validation. He is a man seeking to inhabit notions of romantic anti-heroism, albeit pathetically; we get a sense from the Batman symbol on his door that he might want to be a character out of a noir yarn. But according to Cobb, who immediately deduces that the flat’s occupant is actually unemployed and pretty much a loser, the poor bugger has nothing even worth stealing or talking about. It’s a huge blow to Bill that gets him even more desperate to trade in his blank archetype for a saucier role.

Bill’s maiden burglary goes terribly wrong. Cobb has a darker past that Bill’s failed to consider. A blond femme fatale (Cobb’s girlfriend) plays the victim and lover to Bill, only to screw him over. By the end of the film, Bill has inherited all the trappings of Cobb’s identity, from his roguish confidence to the entire load of his sins, and is indicted for crimes infinitely more heinous than character study. Innocence and freedom was what Bill had taken for granted, until Cobb, thief of a thousand faces, took it away. This is probably why Nolan ultimately framed the narrative as Bill’s confession to a policeman: to show Bill, and the audience, what he had.

Following, above all of its indie cult virtues, showcases Nolan’s fascination with temporally convoluting deceptively simplistic plots—a technique that he would sustain in lengthier works Memento and The Prestige. On first viewing, it seems as if he’s folding the story’s timeline and Freytag’s pyramid into origami-like figures, demanding a fiendish amount of attention and detective-work from the audience. “My most useful definition of narrative,” Nolan has said, “is that it’s a controlled release of information. You don’t feel any obligation to release that information on a chronological basis. What’s interesting about doing this is trying to expand the story in all directions.” Though he prefers tales of delusion and escape, Nolan’s not known for coddling the intellect with his movies.